You need to express yourself to feel safe. We are born with no survival skills except the ability to express pain. When you withhold your urge to be heard, you feel helpless and endangered.

A human infant is the most fragile bit of protoplasm on earth. A newborn gazelle can run with the herd the day after it’s born. An elephant walks before its first meal because that’s how it gets to the nipple. A lizard runs away from home the instant it cracks out of its shell, and if it doesn’t run fast enough a parent eats it. Humans are born with no survival skills except the ability to cry out for help, and to learn from the experience. But we do that well.

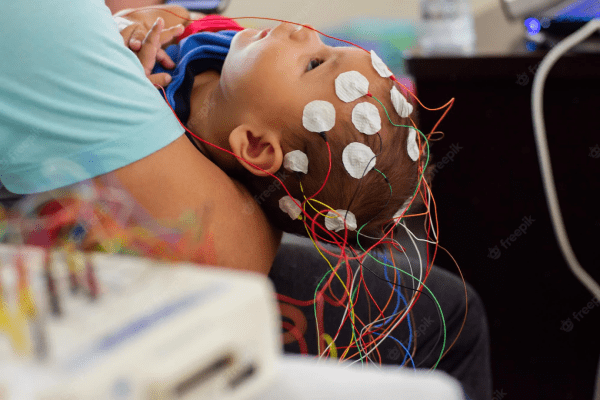

When a newborn cries, it doesn’t know what milk is. It cries because low blood sugar triggers cortisol, the brain’s emergency alert signal. In animals, cortisol activates survival behaviors, like finding food or escaping predators. Humans are not born with survival knowledge. We’re born with lots of neurons, but few connections between them. So a newborn can’t do anything to meet its own needs except cry.

Imagine feeling your survival is threatened and not being able to do anything about it. That’s the state we’re all born into. Fortunately, crying works! Relief arrives. Soon, the baby feels good, and the brain learns from the good feeling. We learn to expect relief, and that gradually transforms crying into conscious acts of communication.

But as soon as you learn that your hunger gets relieved, new emergencies crop up. You learn that the person who relieves your distress sometimes disappears! You experience pain when your body suddenly falls! Pain and the expectation of pain trigger cortisol, and all you can do is cry. So the first experience in each brain, the foundation on which all later experience rests, is the sense that you will die if you are not heard. A baby doesn’t think this cognitively. It feels it in the wordless neurochemical way that an animal experiences survival threats.

And that is why part of your brain longs to be seen and heard as if your life depended on it.

More complex ways of reacting to cortisol grow with time. An adult may not even notice the insecurity at the core of their brain’s experience. You may think you’re better off without your primal feelings of vulnerability. But they are part of being human. The more you know where they come from, the less effort you waste finding things to blame them on. Understanding our primal fragility is very freeing.

Why would natural selection produce a creature as preposterously fragile as a human infant? It appears that brains grew bigger in utero as mothers got more fat. A big-brained fetus has to get born sooner or it wouldn’t fit through the birth canal. We get born so soon that our nervous system has not finished hooking itself up. A full-term human infant is oddly similar to a chimpanzee born a few months premature.

Our prematurity has some curious advantages. First, it left babies so fragile that only the strong communicators survived. Mothers good at interpreting their infants’ signals kept their DNA alive. Communication skills were naturally selected for.

Second, we get to learn survival skills instead of coming pre-programmed for survival in a specific environment. Animals die when they leave their home range, but humans can learn to live almost anywhere.

But we pay a high price for this ability to learn. We have to learn everything. When a baby sees a hand in front of his face, he doesn’t know he’s attached to it, much less that he has the potential to control it. A baby must learn about his hands from experience.

The bigger a creature’s brain, the longer its childhood. A newborn mouse takes two months to learn the skills needed to survive on their own, while a human take two decades. The more neurons a creature has, the longer it takes to do something useful with them.

Extra neurons make it harder to survive because they require so much energy and oxygen. Neurons only promote survival if you really get your money’s worth out of them. That means connecting them up from life experience so you’re not limited to the knowledge of your ancestors.

Babies are good at creating neural pathways in response to experience. For example:

1. Babies coat their neural pathways with a fatty substance called myelin, which is like the insulation on wires. Myelinated neurons are much faster and more efficient than other neural pathways. Myelination happens readily at birth and at puberty.

2. Babies prune their brains. A two year-old has fewer neurons than a newborn, and that helps it focus on learned experience instead of spreading its attention everywhere. A toddler’s unused neurons start to atrophy, encouraging electricity to flow through established neural pathways instead of firing all over the place.

3. Babies learn from pleasure. Happy neurochemicals are triggered when an infant’s distress is relieved. Dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin develop synapses each time they are released, building connections to everything associated with the relief. We wire ourselves to feel good when we see anything associated with good feelings in the past.

The adult brain has some neuroplasticity, but we evolved to build our neural network in youth. The mental model of the world that you built as a child is the model you are still working with. Your early expectations about meeting your needs are still there. You might wish you could change them, but your brain resists using new neural trails when it already has a neural superhighway.

Like every creature in nature, you were born to go out and meet your own survival needs. As you go through life, the world doesn’t always meet the expectations you’ve built. Sometimes your cortisol flows and your survival feels threatened. You find mature ways of crying out for support, but it often seems that your cries go unheard. Instead of concluding that something is wrong with the world, it helps to appreciate the vulnerable organism you started out as.

More on your brain’s early social learning in my book Habits of a Happy Brain: Retrain your brain to boost your serotonin, dopamine, oxytocin and endorphin levels .