Relationships

Videos, Podcasts and Blogs on Relationships

Love Chemicals video

Bustle: 13 Toxic Habits that Make Dating Hard

Dating Like a Monkey podcast

Hitched podcast

Cheat-Proof Your Marriage article

Infatuation interview

Untangle: On Love & Valentine’s Day pod

Oxytocin vs Cortisol blog

Why Love is a Neurochemical Roller Coaster slide show

What About Love? excerpt, Habits of a Happy Brain

Falling In Love Yahoo news

Masculinity and Status podcast

The Neuroscience of Relationships slideshow

Art of Manliness podcast

Relationships @BrainHub SF live talk

Why Love Is a Roller Coaster blog

Attachment podcast

Couplehood is very triggering to our mammalian brain chemicals.

Your happy chemicals respond to whatever promotes your genes, even though we don’t think that consciously. Your threat chemicals surge when you see an obstacle to your “reproductive success,” even if you’re not consciously focused on reproduction. These chemicals are controlled by neural pathways built in youth. Yikes! Stop blaming your partner for your ups and downs and start recognizing their natural origins.

- The good feeling of oxytocin is triggered by touch and trust. But the chemical is soon metabolized so your brain looks for ways to get more. Disappointment is a threat to your mammal brain, which triggers your cortisol. No wonder it’s hard to keep the oxytocin going!

- The good feeling of serotonin is triggered by social importance. No one likes to see this in themselves, but in the animal world it’s easy to see that social dominance promotes survival. Natural selection built a brain that rewards social dominance with the good feeling of serotonin. People get on each others’ nerves because each brain tries to stimulate serotonin in ways that worked for it before.

- The good feeling of dopamine is triggered by finding what you seek. Old rewards do not stimulate dopamine in this brain we’ve inherited. It saves the great feeling of dopamine for new and improved rewards, which is why we huamns are always seeking something.

Book excerpts on relationships

Modern society is often blamed for the frustrations of dating and couplehood, but monkeys had the same frustrations millions of years ago. Below are excerpts on the mammal brain’s response to couplehood from these three books:

Habits of a Happy Brain

Retrain your brain to boost your serotonin, dopamine, oxytocin

The Science of Positivity

Stop negative thought patterns by changing your brain chemistry

I, Mammal

How to make peace with the animal urge for social power

Excerpts from Habits of a Happy Brain: Retrain your brain to boost your serotonin, dopamine, oxytocin and endorphin levels

Each happy chemical rewards love in a different way. When you know how each one is linked to reproductive success, the frustrations of life make sense.

Dopamine is stimulated by the “chase” aspect of love. It’s also triggered when a baby hears his mother’s footsteps. Dopamine alerts us that our needs are about to be met.

Female chimpanzees are known to be partial to males who share their meat after a hunt. Female reproduction depends heavily on protein, which is scarce in the rainforest, so opportunities to meet this need trigger lots of dopamine. For humans, finding “the one” makes you high on dopamine because a longer quest to meet a need stimulates a longer surge.

Oxytocin is stimulated by touch, and by social trust. In animals, touch and trust go together.

Apes only allow trusted companions to touch them because they know from experience that violence can erupt in an instant. In humans, oxytocin is stimulated by everything from holding hands to feeling supported to orgasm. Holding hands stimulates a small amount of oxytocin, but when repeated over time, as in the case of an elderly couple, it builds up a circuit that easily triggers social trust. Sex triggers a lot of oxytocin at once, yielding lots of social trust for a very short time. Childbirth triggers a huge oxytocin spurt, both in mother and child.

Nurturing other people’s children can stimulate it too, as can nurturing adults, depending on the circuits one has built. Friendship bonds stimulate oxytocin, and in the monkey and ape world, research shows that individuals with more social alliances have more reproductive success.

Serotonin is stimulated by the status aspect of love– the pride of associating with a person of a certain stature. You may not think of your own love in this way, but you can easily see it in others. Animals with higher status in their social groups have more “reproductive success,” and natural selection created a brain that seeks status by rewarding it with serotonin. This may be hard to believe, but research on huge range of species shows tremendous energy invested in the pursuit of status. Social dominance leads to more mating opportunity and more surviving offspring– and it feels good. We no longer try to survive by having as many offspring as possible, but when you receive the affection of a desirable individual, it triggers lots of serotonin, though you hate to admit it. And when you are the desired individual, receiving admiration from others, that triggers serotonin too. It feels so good that people tend to seek it again and again.

The link between dopamine and survival is not always obvious. For example, computer games stimulate dopamine, even though they don’t meet real needs. Computer games reward you with points that your mind has linked to social rewards. To get the points, you activate the seek-and-find mechanism that evolved for foraging. You keep enjoying dopamine as you keep approaching rewards. The dopamine paves a pathways that tells you to expect good feelings from computer games. The next time you feel bad, the game is one way your brain knows to relieve those bad feelings. From your mammal brain’s perspective, it relieves the threat, though the social rewards may prove more elusive.

Endorphin is stimulated by physical pain. Crying also stimulates endorphin. If a loved one causes you pain, the endorphin that’s released paves neural pathways, wiring you to expect a good feeling from pain in the future. People may tolerate painful relationships because their brain learned to associate it with the good feeling of endorphin. Confusing love and pain is obviously a bad survival strategy. Roller-coaster relationships are easier to transcend when you understand endorphin.

The sex hormones, like testosterone and estrogen, are central to the feelings we associate with love. They are outside the scope of this book, however, because they do not trigger the feeling of happiness. They mediate specific physical responses instead.

Why did the brain evolve so many different ways to motivate reproductive behavior? Because keeping your DNA alive is harder than you’d think. Survival rates are low in the state of nature, and mating opportunities are harder to come by than you might expect. Your genes got wiped off the face of the earth unless you made a serious effort. Of course, animals don’t consciously intend to promote their genes. But every creature alive today has inherited the brain of ancestors who did what it took to reproduce.

Unhappy chemicals creep into your life as you seek love in all its forms. Animal brains release cortisol when their social overtures are disappointed. The bad feeling motivates the brain to “do something.” It reminds you that your genes will be annihilated if you don’t get busy. You don’t need to tell yourself that in words. Natural selection created neurochemicals that give you the message non-verbally.

Losing love triggers a huge surge of unhappy chemical. That actually promotes genetic survival because the pain you associate with the old attachment leaves you available for a new attachment. The brain has trouble ending attachments because the oxytocin pathway is still there. But if you can’t break an attachment, your genes are doomed. The pain of lost love re-wires your brain so you can move on. Cortisol promotes love by helping you avoid places where you’re not getting it.

Love often disappoints for a subtle reason that’s widely overlooked. A young child learns to expect others to meet their needs. Children cannot meet their own needs, so love equals survival to the young brain. Eventually you have to start meeting your own needs. When the expectation of being cared for is disappointed, it can feel like a survival threat. Childhood is a luxury evolved by mammals, but it comes with a painful transition from dependence to independence. Lots of cortisol is triggered as you learn that you cannot trust the world to meet your needs for you. This independence is natural, for a species can only survive if each generation learns to meet its needs without its parents. And if you had parents who were not trustworthy in the first place, you had more cortisol, sooner. The sense of disappointment and loss motivates people to let go of childhood expectations and find love in adult ways. And that keeps our genes alive.

When disappointment in love gives you that bad cortisol feeling, your brain looks for ways to trigger good feelings. There are limitless ways to do that. Sometimes a person seeks a new mating partner, and sometimes a person focuses on nurturing children. Sometimes a person tries to contribute to mankind at large and sometimes a person uses violence to hold onto their “loved” ones. These behaviors seem very different, but they are all motivated by the expectation of happy chemicals. Expectations depend on the circuits each individual has built from life experience.

In modern times, many people expect romantic love to be part of their life all the time. Expectations were different in the past. Sex created children, and if you lived to middle age, you could expect to be surrounded by grandchildren. But people had the same basic neurochemistry. No matter how you learn to trigger happy chemicals, each burst lasts for a short time and you have to do more to get more. Maybe that’s why love songs are always popular. They activate neurochemicals with fewer messy side effects.

Love triggers a cocktail of neurochemicals because it’s so highly relevant to survival. But it cannot guarantee non-stop happiness. It feels like it can while you’re enjoying the cocktail, however, so your brain may learn to expect that.

From The Science of Positivity: Stop Negative Thought Patterns By Changing Your Brain Chemistry

At the Valley of the Monkeys in France, perky French zookeepers are explaining sexual selection to the public. It was feeding time at the mandrills when I arrived, and I was not disappointed. A keeper was telling the crowd that female mandrills try to mate with the male whose colors are brightest. Male mandrills have rainbow-colored fur on their derrière, and similar coloring on their faces. Males get this coloring to please females (plaire aux femmes), the keeper explained. In nature the colors are brighter than they are in a zoo (she points to a photo of this) because mandrills live in larger groups, so they must compete harder for female attention.

This sex talk was more colorful than I remembered from my first visit! The real subject was bigger than sex, of course. The keeper was acknowledging that competition is inherent in nature. This fact is taboo in California where I live, so I was thrilled to know you can say it publicly in France.

As the keeper explained the ins and outs of mandrill life, I heard many traits characteristic of baboons. I asked her about this and she told me that mandrills are less violent than baboons. Baboons compete for mating opportunity by fighting, but mandrills evolved a way to signal strength with color. They don’t need to actually fight because they compete with appearances instead.

When humans compete with appearances, it may seem annoying. But if you think of it as a substitute for violence, you can see the good in it.

But a mandrill’s life has plenty of frustration anyway. Drab gray males sit around watching more colorful guys get all the action. Females end up frustrated because they all go for the same guy. Biology has something to teach us.

The luminosity of a male mandrill’s fur is caused by hormones that rise as his status in his group rises. A stronger mandrill gets more respect and more food, which gets him more strength and more deference and thus more food. Cooperation can raise his status too, but only if he cooperates with a guy who succeeds at ousting a rival. Mandrills are always trying to avoid painful conflicts. They threaten, they predict the outcome, and they settle. Good moves lead to brighter fur and more copies of your genes. A brain that’s alert for advantage is naturally selected for.

Female mandrills also compete for food because more strength leads to more surviving offspring. They cooperate sometimes when it gets them food or avoids pain. Stronger females get more attention from the colorful males and thus give their offspring the best genes. Natural selection built a brain that learns from what works.

A mandrill is not thinking about its genes. It is just trying to do what feels good and avoid what feels bad. It feels good when it gets food and social support, and that works for its genes. A lot bad feelings are triggered in a mandrill’s quest for things that feel good. A mandrill doesn’t say “something is wrong with the world” when it is disappointed. It doesn’t abstract and generalize because its cortex is too small. It just keeps trying to stimulate happy chemicals and avoid cortisol.

In the modern world, acting on your mammalian impulses can get you into trouble. We use our big cortex to think twice and seek alternatives before we act. But your neurochemical self is always there underneath the verbal abstractions. It is always looking for ways to stimulate your happy chemicals and avoid cortisol, basing its predictions on your past experience. You are not consciously thinking about your genes. But any way of leaving your mark on the world triggers a big spurt of happy chemicals and gets your attention. You only have a limited amount of time to spread your unique individual essence. However you define that, you encounter obstacles as you strive for it, which trigger lots of cortisol. Sometimes you conquer them, but new obstacles appear. Your brain keeps trying to stimulate good feelings and avoid cortisol as long as you’re alive.

From I, Mammal: How to Make Peace with the Animal Urge for Social Power

Before mating, every species has some preliminary qualifying event. The males of most species make great sacrifices for any reproductive opportunity that comes their way.

We have all seen images of two deer locking antlers while a fertile female stands by. Deer fight to the point of serious injury because immortality is at stake. The winner always gets the girl. What does she see in the brute?

A female deer wants the strongest male so her baby will have the strongest genes. When suitors joust in front of her, she gets all the information she needs.

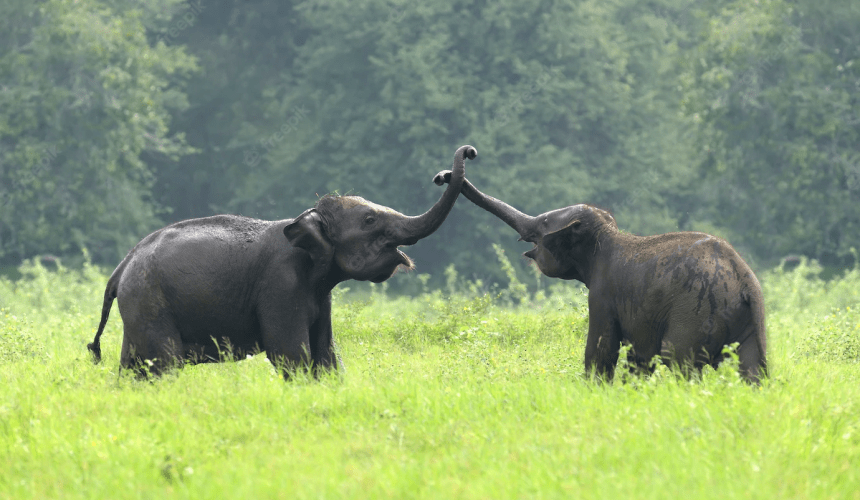

There are other ways for female mammals to weed out the weaker progenitors. Female squirrels simply run away from their male suitors. Only the fastest male squirrels get the girl. The strongest female squirrel can escape all but the strongest males. Her children thus benefit from the strongest genes. Female elephants likewise qualify their suitors by running away. Both genders invest great effort in these chases for reasons we can only speculate about.

Every mammal is the product of its ancestors’ mating choices. When Darwin spoke of natural selection, he was more focused on the competition for mates than the competition for food. Successful food-seeking only promotes survival for a day, but successful mate-seeking promotes survival for a generation. Biology teachers have tended to downplay the conflict over fertile females because it can be hard to discuss in a high school classroom. So we tend to underestimate the degree to which sexual selection is the engine of evolution. The fact is that some individuals contributed a lot more to the gene pool than others.

Mating behavior is produced by happy chemicals and sex hormones working together. These chemicals produce the feeling that you must have Mate X to be happy, but you could do without Mate Y. In this chapter, we will focus exclusively on the status aspects of mate selection. In the mammal world, status is both the means and the end: your status is the means to getting the attention of Mate X, and status helps explain why Mate X has caught your fancy. Of course, no human would consciously embrace this cynical view of mating behavior, but the following up-close and personal look at animals’ mating choices shows a pattern that’s too consistent to ignore. Sex and status go together in the mammal world.

This chapter explores diverse animal mating strategies, including harems, male rivalry and pair-bonding. Within all the variety is a common pattern: sex is the reward for status, be it the quantity or the quality of mating opportunities.

Mammals are quite particular about their mates. They don’t run off with just anyone. All this pickiness ends up improving an individual’s prospects of keeping their DNA alive. The mating market gets sorted out without words because the mammal brain evolved to make social judgements.

There is no free love in the animal world. If there were, more babies would be born than an environmental niche could support. Many babies would die, and the whole species would be at risk if it overloaded its ecosystem. Successful species have evolved behaviors that lead to fewer offspring but higher survival prospects for each one. Mate selection is one of those behaviors. Before mating, every species has some form of preliminary qualifying event.

These events influence which sperm fertilizes which egg and thus which mammals get born.

Every primate eventually has to deal with the adult social hierarchy without the shelter of its parents. When you are the one facing a social hierarchy on your own, it’s unnerving, even though every primate goes through it. Our teen years bring the awareness that we are constantly being judged by our peers, and that we have to manage this aspect of life for ourselves. Each brain constructs a model of how to interact with people outside the family. Each mind learns what it can about how to gain status. Frustration is inevitable as we see others getting Biologists use the term “tournament species” for mammals that joust to determine status for mating purposes. Male tournaments may look like they’re just display, but research shows that they are often ruthless ordeals that sap a huge chunk of a male’s energy and body weight. Losers get nothing for their trouble, and even winners get injured. In the wild, injuries are not patched up by vets and zookeepers; they may bleed, fester, cripple and kill a guy, or weaken him to the point where he’s soon picked off by a predator. In short, the males of most species make great sacrifices for any reproductive opportunity that comes their way.

Any male can refuse to participate, but then he won’t pass on his DNA. We have inherited our brains from individuals who played and won in the reproduction game. A male who failed to reproduce cannot be our ancestor. and learn that we cannot always dominate. This dilemma is universal, but we feel the frustration individually. Each time a young person is happy, their brain stores the experience as a guide to finding future happiness. Each time they are sad, their brain extracts lessons about what not to do. Without conscious effort, the adolescent brain builds a mental model of social dominance. Experiences relevant to a teenager are the raw material of this model. Where to sit at lunch and what to say in class may not seem relevant to later life, but the brain automatically extracts the patterns.

For the ladies, the tournament system also has its advantages and disadvantages. To humans, it may seem that the system restricts a girl’s freedom of choice. But tournaments have curious advantages for females. They give every girl her species’ equivalent of the captain of the football team. Every girl gets a guy who fought for her.

A scientific explanation of these benefits is known as the sexy son hypothesis. Serious biologists coined the phrase to underscore the reproductive math. A male mammal can have a large number of offspring in his lifetime if he becomes an alpha, but a female’s reproductive potential is much more limited no matter how high her status. She nurses each newborn for such a long time that she can only have a few in a lifetime. So how can a female’s reproductive success match a male’s? She can give birth to a son who grows up to be an alpha, thus making many copies of her genes. And the best way to have a son who’s a big stud is to select a father who’s a big stud.

As primates grew larger brains, their reciprocal strategies grew too. Males began appealing directly to females instead of going head-to-head with the patriarchy. Male chimps are known to appeal to females in ways that are familiar to humans. To put it frankly, chimps in the primeval forest have been found exchanging meat for sex.

The motives for this exchange are not obvious. Let’s begin with the female perspective. A female takes a risk when she mates with a gift-giving male because the alpha male could retaliate against her or her children. This tells us that meat is a strong motivator for her. It turns out that a mother’s protein and fat consumption influences the size of her newborn’s brain. Meat is scarce in the jungle.

Insects supply survival amounts of protein, but meat can boost nutrition significantly. Over time, females who attracted meat-bearing gentlemen callers wound up with bigger-brained children. This delicate transaction may be the very engine of human evolution.

Now let’s consider the male perspective. A low-status male chimp has a hard time getting meat. Male chimps hunt in groups that dole out their kill in rank order. An alpha male can always grab meat from other males and they don’t resist. A low-status male ends up with a smaller share of meat, and he needs the nutrition himself if he’s to build up his fighting strength. Is he better off sharing his meat with a female or eating it himself?

In truth, it must be reported that a lot of begging goes on in primate communities. When a male returns from the hunt munching on a piece of meat, females beg persistently. Ovulating females beg most enthusiastically. To some extent, males share meat in order to be left in peace to eat the rest.

Reciprocal exchange is not necessarily an explicit transaction. Two individuals may have a very casual interaction without conceptualizing the future. But if they interact repeatedly, neural pathways for trust gradually build. Trust circuits motivate sharing without a conscious intent to give and get. An ape simply releases oxytocin in the presence of another ape. Networks of familiarity can develop alongside the formal status hierarchy.

Such reciprocal bonds are not driven by meat alone. Grooming and babysitting are popular alternative forms of giving. Offering to groom is a well-documented primate strategy for cementing relationships. Female baboons who experience the death of a close female relative are observed to respond by initiating groomings with new partners. Grooming typically reflects the status hierarchy, but it is also a tool for raising status. Young males groom older males to accelerate their climb up the dominance hierarchy. Young females groom older females to build support.

Reciprocal exchange is not necessarily an explicit transaction. Two individuals may have a very casual interaction without conceptualizing the future. But if they interact repeatedly, neural pathways for trust gradually build. Trust circuits motivate sharing without a conscious intent to give and get. An ape simply releases oxytocin in the presence of another ape. Networks of familiarity can develop alongside the formal status hierarchy.

Primate grooming is not always reciprocal. A lower-status individual often grooms a high-ranking individual without getting an immediate return. But the groomer gradually develops an ally in case of future conflict.

When there’s open conflict between two primates, the winner is typically the one with the most allies. When a baboon or chimpanzee gets into a fight, it makes a distress call that the others recognize. Cheney and Seyfarth documented this selectivity by recording individual calls and playing them back to individual group mates. They found that baboons respond to the calls of those with whom they have developed longstanding bonds of reciprocal exchange. Primates do not risk their lives to protect just anyone, but they rush to protect individuals with whom they have spent a lot of time grooming. When you spend a lot of time around an individual, you create neural pathways that register their alarm call instantly.

Monkeys and apes seem to have an amazing ability to keep track of the favors they owe and are owed. My parents did the same thing when I was growing up. I noticed them keeping track of gifts given and received in order to maintain reciprocity. This custom is widespread in traditional societies. Animals manage to do it without explicit cognition. Repeated contact simply creates neural circuits, and behavior follows.

Researchers find that fertile females favor males that repeatedly groomed them in the past. Monogamy is rare in the primate world, but repeated grooming develops into neurochemical attachment. When a primate receives a grooming, its brain links the good feeling of oxytocin to the individual grooming it. Oxytocin circuits condition a primate to expect this good feeling when it sees that individual.

The hard data on grooming show that much of it occurs among males. Lower-ranking males tend to groom higher-ranking males. The resulting bonds help males cooperate while hunting or defending their territory from neighboring troops. Higher-ranking males do not need to groom others because they have the strength to win conflicts. Weaker males initiate groomings to build good will with the males that dominate food and sex. This gives a low-ranking male a choice of strategies for advancing his reproductive prospects. He can build muscle, court the male power structure, and/or court ladies directly. A brain good at choosing the best strategy at each moment is likely to get passed on.

Love and Monogamy as Success Strategies

Relationships can be brutal for monkeys. A male might provide meat and babysitting to a female only to see her favor others come mating time. An alpha male can spend days guarding an estrous female, only to lose the match during a moment when his attention is elsewhere. Disappointment triggers unhappy chemicals, which prompt the brain to look for an alternative.

“Love” is one alternative that evolved. If a partner only has eyes for you, your DNA has an advantage. Getting another to fall in love with you is a great reproductive strategy.

Chimpanzee researchers occasionally find such consortships – exclusive bonds that last the whole length of a female’s ovulation. That isn’t long-term from a human point of view, but such exclusivity is rare among chimpanzees and bonobos. Researchers eagerly analyze these trysts for answers to the big questions of life. From the far end of a telescope it looks like love, but let’s look at a mundane neurochemical explanation.

Female chimps usually mingle with the alpha and the high-ranking males of the troop during their fertility periods. But researchers occasionally find a female chimp sneaking off with a lower-status male. Top-ranking males tend not to engage in exclusive consortships because their status in the male hierarchy is at risk while they are away. Why would a female go off with an underling and give up the chance to raise her standing with the ruling clique?

Why would she give up the chance to beg many males for meat and hide silently with one beau on the outskirts of the troop’s range, exposed to the risk of attack by raiding parties from neighboring troops? Inquiring minds wanted to know, and they got research grants to find out.

They found some evidence of coercion, and some evidence of dopamine and oxytocin. Researchers are still trying to discover why those happy chemicals get triggered. What makes this particular mate so special? A female may be attracted by a scent that’s different from hers. It seems to mark the male as genetically diverse. Did the male with the right smell just get lucky? Researchers are hotly pursing this apparent end run around the status hierarchy.

In any case, chimpanzee consortships do not last. After a few days, the couple goes back to the way they were. A male chimp isn’t predisposed to “babysit” for his own flesh and blood. Lasting pair-bonds are rare among mammals, except for the few species whose brains naturally produce high levels of oxytocin.

Monogamy is the norm for a few oxytocin-rich mammals, including one ape: the gibbon. But even mating for life doesn’t stop gibbons from focusing on dominance. They simply treat it as a couples activity. Their relationship is an alliance to raise their dominance together. They start working at it first thing every morning.

Gibbons make loud calls for a half hour when they wake up every morning. They jointly scream their heads offs to scare other gibbons off their turf. Then, Mr. and Mrs. Gibbon start patrolling in case other gibbons failed to get the message. Their children join in these enterprises.

Trouble in paradise is never far away. When other gibbons hear the duet of a mated pair, they judge it. If the sound is not strong and well-coordinated, neighboring gibbons interpret it as a weakness. Unattached singles enter the family’s domain. Soon, Mrs. Gibbon may be starting a new family with another man. When the intruders are female, Mrs. Gibbon quickly attacks if she sees them approach her mate. Scientists have found high levels of aggression in the female gibbon. Her children’s survival depends on keeping all the territory’s nutrition for them rather than sharing it with the other woman’s baby.

Once again, sex and dominance go together. Olio Lusso JustCBD Loxa Beauty